BOTANICAL ENCOUNTERS: Rewilding The Kalahari - The Land

- k-england

- Jul 31, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Aug 2, 2025

Words and pictures by Ida K. Rigby, for Let's Talk Plants! August 2025.

Rewilding The Kalahari: The Land

Our title photo will remain a mystery until later into the essay. Tswalu Kalahari Reserve shows how nature heals herself given a chance. The transition from overgrazed dunes and flatlands to a comfortable habitat for a range of fauna and flora is evident in the variety of creatures that now populate the area and habitats that have regenerated. The checklist I received in 2019 lists mammals (96), birds (over 240), reptiles (53) and flora (123) confirmed on the reserve. More will be found, such as the discovery in 2023 of the eighty-third species of butterfly on one of the hilltops; this attests to the ever expanding biodiversity of the restored hills, plains and dunes. It requires careful management, surveillance, and scientific research to establish and keep a balance. The Tswalu Foundation (founded in 2009) supports ongoing research by international experts with a focus on research that can inform conservation practices on the reserve.

The count of butterflies is a particularly interesting indicator of the restored diversity of flora as butterfly caterpillars are highly specific in terms of the plant they need to survive. (Terblanche, tswalu.com) Of particular importance are the 10 plants that sustain the annual Kgalagadi Butterfly Migration across southwest Africa. Some caterpillars live underground and need a specific host plant plus a specific guardian ant to survive. The ants accompany/protect the foraging caterpillars.

An overview shows the restored grasslands and savanna plains surrounded by rocky hills. The restored savanna offers nesting for weaver birds, browse for giraffes and antelope and shade for kudus.

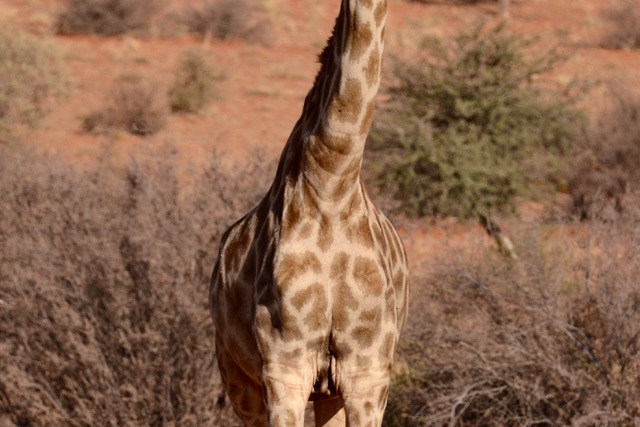

Resting kudus will each face in a different direction so they can smell the scent of predators on the wind. Restored plant life is the foundation for wildlife, providing food, shelter, shade and camouflage. As an aside, giraffes can chew their cud standing up! It seems improbable, but we watched, what you can barely see...

... as a round mass that seems to inflate the giraffe’s neck as the cud moves up then down the height of the giraffe’s throat. If you have ever watched a giraffe trying to stand up you know how vulnerable they are when resting on the ground or spreading their legs to drink.

The restored vegetation provides camouflage and hiding places for prey...

...and predators alike.

These lion cubs are staking out a path to a water hole.

The rocky hillsides provide hiding places and cool dens for rodents. They also provide camouflage for kudu.

A leopardess and her two cubs lived in the rocky hillside adjacent to the lodge. She would come down to hunt during the night. We saw her near the lodge one evening. These hillsides were also home to Hartmann’s mountain zebras but they were too far away to photograph. They are sturdier and have a different striping pattern from plains zebra. A herd of zebras is called a dazzle of zebras. The idea is that the patterns of stripes can “dazzle” a predator into being unable to pick out individual animals to attack. The grasslands provide a congenial home for the more common, plains zebra.

Some more remote rocky hills also have succulents such as mountain euphorbia (Euphorbia avasmontana).

The success of the restoration of the black rhino habitat of grey camel thorn (Acacia haematoxylon), according to our guide, has resulted in increasing the reproduction rate of the black rhinos.

A group of rhinos is called a crash of rhinos (no explanation needed). Our days ended with a drive home under a super moon.

One morning our guide announced that he had a special treat for my niece and me, a walk and reading the story of the land. We started at a water hole and ended up at a rock art site at the base of the mountains in the distance, some two hours away.

The land is the daily newspaper where you can read the events of the might before as well as the layers of history that have been laid down over the millennia. He asked us to imagine being a San girl collecting water for her family and then returning the two hours to their current campsite. We would, he said, follow the paths made by the larger mammals. They were narrow ruts, worn into the soil by centuries of use but paths used by the wider mammals so humans could pass without getting caught in the acacia thorns.

We first passed a rolling pit where zebras took dust baths and where we saw baboon footprints (one he outlined so we could clearly see it).

We learned a little about tracking by studying hoof and paw prints. Poop pellets also let you know who has passed by, from the white hyena feces (white because their powerful jaws crack bones and allow them to eat left-over bones from kills) to the dainty duiker dung. Our guide pointed out where a scorpion had made a den next to an ant lion trap.

This four-year-old ant lion larva ...

...has made a slippery sloped cone. When the sand is disturbed and the prey falls in the ant lion emerges to capture it. We soon passed a mud termite mound.

Now it’s time for the answer to the mystery article cover image.

The wind blows the grasses, sometimes in a complete circle and they etch a pattern into the sand. They are often crisscrossed by antelope, rodent and beetle tracks. We passed acacia trees that provided homes for weaver birds, ...

...and shepherd’s trees that offered nooks for sheltering small creatures...

... and perches for a gabar goshawk.

During our hike we came upon remains showing different ways of relating to the land in the remains of the ancient and recent history of this area. A pile of rocks was left by the nomadic San and simply becomes part of the landscape.

Its use is unknown. At the left of the photo is one of the narrow paths created by passing large mammals and formerly humans. The spot is anchored by a shepherd’s tree where the San would have stopped for shade, a rest, and perhaps to meet and tell stories. More recent rock markings were property boundaries made by Afrikaner landowners.

Our guide pointed out the difference: Whereas the San rocks have scattered and rest gently on the land, the Boer boundary markings cut a harsh scar across the Kalahari sands. The boundary walls also marked out the small areas between properties where the San farm workers were confined in without access to their traditional water holes without permission to cross private property, a term foreign to them. The rock and concrete dam is also a heavy fixture on the land, again so different from the light and evanescent touch of the San.

After two hours we came to the foot of the mountains and etched markings on an area, which in the rainy season is a waterfall.

Into the rocks are etched images of eland...

...and ostriches.

(The photo of ostriches was taken in Namibia, not Tswalu.)

The male eland sports a red hairy growth on its muzzle. There are also etchings, like the circles, whose meanings are lost. Near the seasonal creek are the remnants of semi-permanent dwellings in the rock walls.

They were probably occupied when the creek ran and there was ready access to water.

One researcher at Tswalu, Benjamin Schoville, (tswalu.com) notes that there are traces of 500,000 years of human activity at Tswalu, from the Stone and Iron Ages. Most are near former water sources. Human adaptations to climate change can be read in these archaeological remains. They can be found in calcrete quarry walls in areas that were once lakes and scattered in seasonal pans. They include stone axes and quartz arrowhead tips from quartzite sources in the nearby Korannaberg hills.

There are a number of studies at Tswalu that relate to climate change. One researcher, Grace Warner, examined how micro shelters might figure in creatures’ adaptation to increasing temperatures in an area where they are already living on the edge. (tswalu.com) She cites tree cavities for cape cobras, aardvark burrows (which are used by three different vertebrate species including warthogs, porcupines, hyenas and African painted wolves), shade, rocks, dens, and sociable weaver nests as microclimates that can provide shelter from warming temperatures.

On one of our drives we witnessed the, often to human eyes, curious mating performances of a male bird. The restored shrubbery is now a congenial habitat for the red crested korhaan.

The bird was performing a limping strut and flashing his red crest, which was followed by a vigilant stance. The lady on the other side of the shrubbery was playing hard to get. Another savanna bird, the kori bustard (national bird of Botswana) is back on these plains.

It is the heaviest flying bird in Africa.

As we saw in an earlier column, the baobab is home to a panoply of life. The camel thorn, thanks to the sociable weaver bird supports a similar, although not as extensive, community. The sociable weaver birds build huge communal structures housing hundreds of weavers and other birds and reptiles.

They live in individual family units but collectively maintain the structure on an ongoing basis. The apartments create a relatively even temperature in the temperature extremes of the Kalahari. The white poop at the entrance to a nesting area signals the presence of a pigmy falcon.

The weavers are prey for the falcon, but falcons are tolerated because they also capture snakes, like the cape cobras that also inhabit the colony. Our guide pointed out that we were fortunate to see a pigmy falcon who had just caught a lizard as birders come to try to see this rare falcon.

The presence of sociable weaver nests also influences the environment around the camel thorn tree. In one of the research articles on the Tswalu website, Brian Maritz points out that Kalahari tree skinks prefer trees with sociable weaver nests. He also points out that there is more reptile diversity under trees with sociable weaver nests, accentuating the importance of the restored flora at Tswalu. He also comments that cape cobras and black spitting cobras prefer to forage under the nests as eggs and chicks fall out; they also climb into the nest chambers seeking food. Large mammals, such as wildebeests take advantage of the additional shade offered by the structures, but the large nests...

...also afford perching posts for cheetah and leopards who then leap down on them. (The photo of the nest with the hammock-like structure, which can support a cheetah or leopard, was taken in Namibia.)

Speaking of cobras, in 2014 I did encounter a Cape cobra on one of lodge’s paths. This was only slightly less unnerving than learning at another lodge that the lovely rocky island in the center of the walkways around my dwelling was home to a “very tolerant” black mamba. That same lodge featured a “friendly” Cape buffalo who amused himself by chasing staff members as they came to work in the morning.

During one of our tracking lessons we learned how to find cheetahs. Our guide knew where they were, so he was able to point out to us the signs that they were near. He pointed out their tracks...

...and the smell of fresh urine markings on fallen logs. We climbed back onto the vehicle and of course came upon the two brothers napping during the midday heat.

Note their paws; cheetahs do not have the fully retractable claws of lions, which helps give them more purchase for their fast sprints after game.

One afternoon we took advantage of the shade of a shepherd’s tree to hear our guide tell his story.

He was raised in Mozambique during the civil war (1977-92). His parents had told him if their village was attacked to run away with any group of adults. One night in 1990 during an attack he did this. His harrowing tale included tragedy, losing one of their party to a crocodile while crossing a river into South Africa and loyalty. The four adult males told him, an 11 year old boy, to stay put from time to time while they moved ahead to scout, and every time they returned to reunite with the slower moving child. At one point he stopped his narrative, looked at me, and said “turn around.” A few hundred feet away was an aardvark.

It was a magical moment.

En route to the airstrip on our last morning we came upon an elderly lion in the shade of an acacia shrub.

I like to think he was the same lion who had welcomed me to Tswalu one late afternoon five years earlier with his family of cubs.

Ida Rigby is a past SDHS Board member and Garden Tour Coordinator. She has gardened in Poway since l992 and

emphasizes plants from the northern and southern Mediterranean latitudes. Her garden received the San Diego Home/Garden magazine Best Homeowner Design and Grand Prize in their Garden of the Year contest in l998. Her travels focus on natural history.